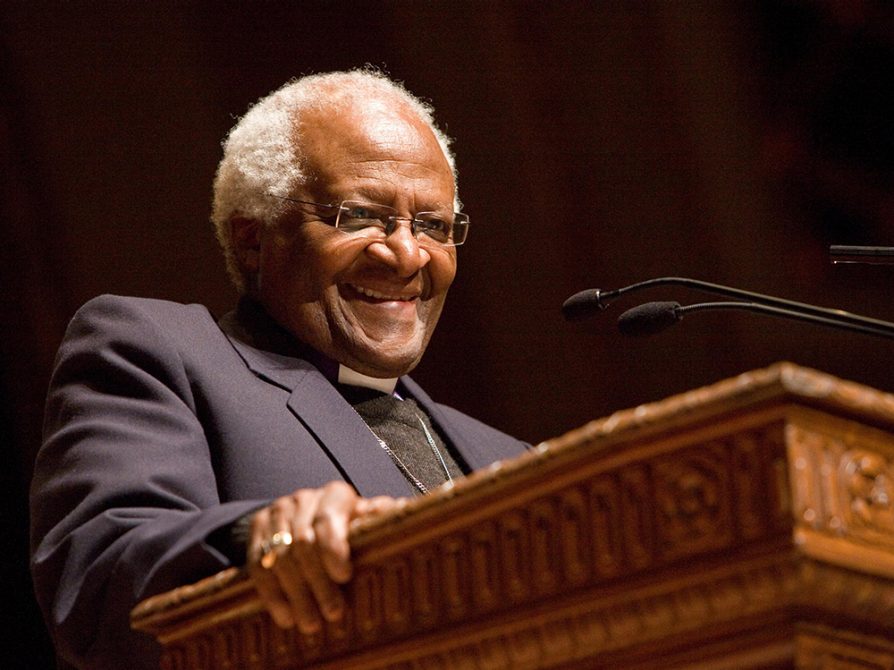

Elizabeth James is sharing some of her favorite moments from her 28-year career as the program associate of the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies (DAAS). In addition to supporting students in the Black Student Union and liaising with students, faculty, alumni, and staff, James also coordinates DAAS’s spectacular calendar of academic events and cultural celebrations. Some of her favorite memories include listening to Alice Walker read in Hill Auditorium, and the brunch she hosted for Desmond Tutu.

“He was a ray of light!” James laughs, remembering the day. “He came dancing out of the elevator, saying, ‘Here are my people!’” A staff member had brought a homemade cake for the occasion, and Tutu couldn’t help himself from “sneaking” thirds and fourths.

But most of all, James treasures the moments with people she works alongside on a daily basis, or did before COVID-19. “I miss hearing our scholars speaking in the halls in French, in Swahili, or walking by an archaeologist, an anthropologist, a public health expert, and a historian of literature of the American South chatting in the Lemuel Johnson Center like some Jedi meeting! It’s a tremendous honor to work here.”

Professor Matthew Countryman, chair of DAAS at the time of this interview, works closely with James to think creatively when it comes to nurturing connections: between academic disciplines, between alumni and current students, and even between nations because DAAS scholars study and work all over the world. And this year—this unusual, challenging year when the department had planned to celebrate DAAS’s first 50 years—the work of nurturing connections matters more than ever. Not only did Countryman and James need to transition the long-planned anniversary’s festivities online; they also needed to transfer and sustain the energized network of students, faculty, staff, and alumni whose joy, knowledge, and love have guided DAAS’s first 50 years and will guide the department’s future.

But Countryman and James are determined to do it. “DAAS is the little engine that could.” James says. “We are a very small unit, but there is so much joy, knowledge, and love.”

Into the Archives

Stephen Ward, an associate professor in DAAS and the Residential College and faculty director of the Semester in Detroit program, sees the fiftieth anniversary of DAAS as an opportunity to dig into the history of Black student activism at U-M with his undergraduate students.

In his senior seminar, “DAAS in Action,” Ward partnered with Cinda Nofziger, an archivist at the Bentley Historical Library, to introduce the students to the primary sources in the Bentley’s DAAS Collection. As the students familiarized themselves with its databases and materials, they also developed their archival skills, eventually growing comfortable conducting archival research independently at the Bentley.

The stories are there, but the material can be scattered, nonlinear, difficult to put together. “Students want to know how students in the past dealt with social justice issues,” Nofziger says. “We have so much material from our different collections to tell the story of student activism. Tracing these student demands and stories requires looking at different threads,” she says.

Students studied the digitized DAAS collection and pored over handmade flyers from the student-led Black Action Movement in 1970, uncovering sources that told the story of the creation of the Trotter Multicultural Center, the beginnings of DAAS, and the history of the Black experience on campus. Ward, who also teaches courses in African American history, the Black Power Movement, the evolution of hip hop, and the history of Detroit, says he hopes his courses provide opportunities for his students “to learn by doing.”

“Student activism was largely responsible for the creation of Black studies here at U-M,” Ward says, “and largely, the ideas and energies of students will shape its future.”