The Last Video Store

Illustration by Charlie Layton.

It's amazing what you can get done at the video store.

You can price a tractor and rent Field of Dreams at a video store in rural Wyoming. You can rent a tuxedo, buy a cheeseburger, and grab Ferris Bueller’s Day Off from a small town store in Tennessee. Or you can spend a few minutes bronzing your gams before renting the first season of Dukes of Hazzard at one of the many tanning salon–video rental combo stores all across the South.

LSA Screen Arts and Cultures Professor Daniel Herbert has seen them all. His book, Videoland: Movie Culture at the American Video Store, catalogs the ways that our tastes have been changed by video stores and the ways that video stores serve and affect the communities around them.

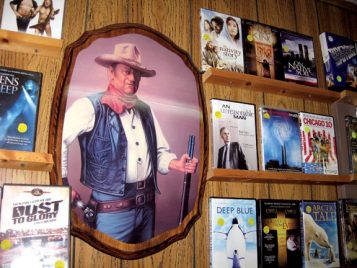

“They reflect the community,” Herbert says. “Stores will have hunting and fishing sections, or Christian sections, or Spanish-language sections, based on what people in that area want to see.”

Video stores also reflect the personalities of their owners, including one in Georgia who sold purebred dogs alongside DVDs. The owner could do this, Herbert says, because the video rental business is so flexible, making many of them one-of-a-kind destinations.

“A video store doesn’t require any specific architecture,” Herbert says. “It can pair itself with a wide range of other activities. So you see local conditions and people’s personalities and tastes coming together in these unique spaces.”

Herbert drove more than 8,000 miles across the country between 2009 and 2011 to interview the people who owned and clerked in small town video rental stores to find out what it was like pointing customers toward the new releases at a time when fewer and fewer people were renting movies.

And it’s good that he went when he did, because pretty soon there might not be any stores left.

Be Kind, Rewind

The year 2010 — when Herbert did much of his research for Videoland — saw the closing and liquidation of Hollywood Video, a national video rental store chain. That same year, Blockbuster declared bankruptcy, and has since closed up all of its shops, down from a high of about 5,000 stores in the early 2000s.

The 2008 recession was part of the problem, but the industry’s biggest problem was competition. New digital options, including on-demand services like Netflix and Amazon Instant Video, as well as digital piracy, posed an existential threat to video stores. While people are gaining the convenience of movies with the push of a button, they’re losing something important, Herbert says.

“In many towns, video stores became a kind of de facto community center because of the habitual ways that people used them,” Herbert says. “You rent a movie, you return it. You rent another one, return that one. You run into neighbors, you talk to the clerks. It becomes a touchstone for your life.

“Losing video stores isn’t about losing movies — movies are doing fine — it’s about the loss of these public spaces where we have an opportunity to share ourselves and learn who other people are,” Herbert says. “Now, I don’t know where those spots are.”

But some large video stores have survived. Some niche stores like Scarecrow Video in Seattle (Herbert serves on the board of Scarecrow) have successfully reimagined themselves as nonprofit organizations, adding an educational component to their mission. The key to video stores surviving might be to embrace what made many of them unique in the first place — the communities they serve. And educating people about movies is important, because with smartphones and tablet computers, movies are now available anywhere.

“They’re good tokens of social exchange because everyone watches them,” Herbert says. “No matter what your educational background is or what your economic background is, you watch movies and you have something to say about them.”