Not All Those Who Wander Are Lost

This is an article from the spring 2016 issue of LSA Magazine. Read more stories from the magazine.

Every year, LSA sends four graduating students around the world, providing them with $20,000 in support, and the only requirement is that they travel. A lot. Recipients of each of the four competitive Bonderman Fellowships are required to travel to six countries in two different global regions over the course of eight months, immersing themselves in local cultures and visiting locales usually left untouched by Western tourists.

The fellowship is named after businessman David Bonderman, who received the Sheldon Fellowship at Harvard University to study and travel abroad over 45 years ago, an experience that he says changed his life. The fellowship exposed Bonderman to the richness of the world and later inspired him to establish a fellowship in the family name at the University of Washington. In 2014, David’s daughter, LSA alumna Samantha Holloway (A.B. ’03), and her husband, Gregory (A.B. ’02), created the Bonderman Fellowship in LSA’s Center for Global and Intercultural Study (CGIS).

Taking its inspiration but not its structure from the U-W program, the Bonderman Fellowship at Michigan is a one-of-a-kind experience. Although CGIS Director Michael Jordan says they don’t look for any type of student in particular, each year they choose four graduating seniors who show an ability to be self-reflective, and who are open to change and spontaneity.

“The people we have selected speak of their desire to get to know things beyond their immediate sphere of familiarity,” says Jordan. “You know it when you see it.”

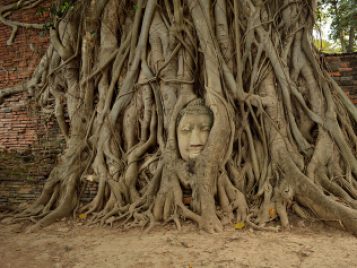

A detail of a sculpture from the Wat Rong Khun, more commonly known as the White Temple, in Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. Photo by Harleen Kaur

Each Bonderman Fellow is provided money and time to travel the globe, with the stipulations that the majority of their travel be solitary to encourage total immersion in the host cultures, and that the fellows visit a set number of countries and regions over the course of eight months. Recipients are also encouraged to explore places less well-traveled by Westerners, but choices about where to go, what to see and eat and read, and how to get from point A to point C to point F—all of that is up to the fellows.

The first thing that many Bondermans feel when they step off the plane in Argentina or Mozambique or Kuala Lumpur is disorientation. Awash in new colors, sights, and sounds, the Bonderman Fellows are entirely on their own to explore, to choose where and how to spend their time. Some stay in hostels, others with local families. Some stick to schedules they’ve made for themselves. Others play it by ear, lingering as they please in each location, waiting for some internal timer to go off before moving on to the next town, the next country.

“You get used to change,” says Tyler Mesman (A.B. ’14), who traveled everywhere from India to Thailand to South Africa on his Bonderman Fellowship. “You adapt every day to new surroundings. Even within one country, cities can be vastly different.”

Although it’s only the program’s second year, seven Bonderman Fellows have already crisscrossed the globe. Along the way, they’ve celebrated Diwali with new friends, visited Bolivian silver mines, and stayed with grape growers in Chile. One fellow ran the Eurasia Marathon from Asia into Europe. Another went snowboarding in the snow-capped Andes Mountains.

Bouncing from country to country, the Bondermans learn to adapt to new foods and smells and foreign tongues, making new friends by forming bonds with locals and other travelers alike. They share meals and laughter, trading stories about their lives, cultures, and hopes for the future. Each of the fellows is happy to recount the generosity of the many strangers they encountered across the globe, remembering the ways in which human kindness can transcend cultural differences. Louis Mirante (A.B. ’14) was touched by the countless invitations he received for meals and lodging from strangers he befriended. Christian Bashi (A.B. ’15) was humbled by a poor Peruvian woman who shared her fruit with him on a long bus ride. Even traveling solo, the Bondermans don’t feel alone.

Statues guard the entrance to Batu Caves in Gombak, Selangor, Malaysia. Photo by Harleen Kaur

“At first, traveling by myself was difficult for me, and even a bit isolating,” says Ashline Hermiz (B.S. ’14). “But then I met so many amazing people along the way who were kind to me when I was in need of a helping hand.”

Despite their very different itineraries, many Bondermans talk similarly about their experiences. The exhilaration of arriving at the first stop on their trip. The surprising moments of humor and largesse they encounter on the road, on a train, or in the air. The pangs of happiness that occur when they encounter something familiar in an unfamiliar country.

Another curious, parallel reaction that many of the Bonderman Fellows go through is a kind of crystallizing of the self, where fellows talk about suddenly understanding much better who they are and what their place is in the world. The nature of the trip means that most fellows are bound to have their identities challenged and shaped by the things and people they encounter, an experience that can be both difficult and illuminating.

Harleen Kaur (A.B. ’15), who is Indian American, says she is accustomed to explaining her background to other Americans. But it came as a surprise when, in China, she was asked if she hoped to return to India someday.

“I’m from Philadelphia,” she says. “At that point, I had only been to India once as a child, and so it was interesting that they perceived me in that way.”

Hermiz, who is Arab American, began seeing her identity in a more nuanced way the longer she was abroad.

“Growing up, I felt not exactly American but not fully Arab either,” she says. “As I traveled, I started to identify more and more with my American nationality and push back against this idea that there is only one image that an American can have.”

Catherine Huang (A.B. ’15), an Asian American, at first took offense to the people staring at her or pulling at their eyes or yelling “Konnichiwa!” at her. But then she began gently confronting these people. To her surprise, she managed to have a number of constructive conversations with the people she approached. “They were curious more than anything,” she says.

For other fellows, the newfound experience of being “different” in a new place, of being out of one’s element, instilled a greater sense of empathy for the challenges of others.

A room full of empty shoes from the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in Poland. Photo by Catherine Huang

“I’m a straight white man,” Mirante says, “and there aren’t too many places that haven’t been built for people who look like me. My experiences traveling gave me a thicker skin, and also gave me more of an appreciation for the problems other people face in our own country.”

The Bondermans come to know the world, and through the world, come to know themselves better.

Amid a whirlwind of countries and cultures, perhaps the greatest discoveries the Bondermans make are about themselves: about their strength to overcome challenges, about their flexibility and empathy, about the importance of slowing down to appreciate life’s tiniest pleasures.

Fellows come back changed, more confident, more adventurous. After she returned from her fellowship, Hermiz, for whom solo travel was once a somewhat frightening prospect, decided to postpone her plans for graduate school in favor of a working holiday year in South Korea. Mesman has some ideas for his future, but he’s no longer in a rush to get there. “The world is a really, really large place,” he says. “What I learned while traveling is that there are multiple routes to success.”

For Mirante, though, the Bonderman experience not only solidified his desire to work for the government and to serve the needs of citizens, but also opened his eyes to better ways to do it.

“I think the most important thing I learned for the career I’ve chosen is that it’s important to be culturally aware,” he says. “Sometimes the things you think are problems may not be problems to other people. On the other hand, they may have problems that you wouldn’t think of if you didn’t ask.”

Christian Bashi has come to savor the beauty of small things, like the sight of hummingbirds in the morning fog at Machu Picchu, or the roar of the crowd at a World Cup qualifying match.

“The hardest thing about returning will be that I will start forgetting,” says Kaur. “I want to figure out how to hold on to the things I experienced and continue processing it all when I’m back in the U.S.”

It’s diffcult to fully capture the Bonderman experience since each fellow’s journey is deeply personal, tailored to their interests and desires. They are united, however, in their eagerness to explore the greater world, and to expand their knowledge of new cultures, peoples, and ideas—all on their own. Without exception, they return home mentally and physically exhausted, but also renewed, ready to take on new challenges and to let life happen as it will.

Bonderman Fellows travel all over the world, with each country, city, and train ride generating memorable stories that the young alumni bring home with them. Here are four tales of wide-eyed discovery and unexpected generosity from the front lines of LSA’s Bonderman Fellowship.

Louis Mirante

Fuvahmulah is a tiny speck of an island in the middle of the vast blue Laccadive Sea south of Sri Lanka. On this atoll, lush green areca palm trees sway gently, heavy with nut-like fruits called betel. For several days, Louis Mirante has been heading to this place on board a small ship that appears as barely a blip on the cerulean waters. Mirante heard from a local Maldivian that Fuvahmulah was close to paradise on Earth with white sandy beaches and verdant wetlands—a place where nearly every home has its own mango tree, and whose population of a little over 12,000 always seems to make visitors feel like family.

After Mirante negotiates a rate of $30 for the three-day journey to the island, he joins a group of fisherman and sets off to sea. At first, things are a little awkward. Although they are kind, the Maldivians are unsure what to make of this American, the first many of them have ever met. During his first evening on the boat, Mirante joins the men for a dinner of fish curry. Many South Asians prefer to eat with their hands, but out of respect for their guest, the men have found the lone spoon on board and placed it next to him. They sit, quietly watching him. Mirante hesitates, then picks up the spoon and sets it aside. Grabbing a hunk of rice and fish, he tosses it into his mouth and begins eating. After a brief pause, the men break into laughter. The tension is gone in an instant, and the men tuck happily into the rest of their meal.

A few days later, the ship arrives at Fuvahmulah, and Mirante leaves his new friends on the ship and heads off, ready for the next leg of his adventure.

Christian Bashi

It is a pitilessly hot August day in the Caribbean, no breeze to break the swelter of the summer sun radiating off the worn streets of Havana.

It is a month after the U.S. Embassy in Cuba has opened its doors for the first time in over 50 years. Christian Bashi is wandering through a park, taking in the sights and sounds of celebration. People are excited for the official opening ceremony the next day. Coincidentally, a Detroit-area news team spots Bashi in his U-M T-shirt and interviews him about how it feels to be there on that historic occasion. Afterward, they invite him to watch the next day’s events with them.

The heat drags on, bearing down on the crowd so intensely that one young boy faints. Bashi can barely hear Secretary of State John Kerry’s speech, but he can see the raising of the American flag and he feels the swell of emotion as he joins the crowd of thousands of Cubans singing the American national anthem.

Ashline Hermiz

Ashline Hermiz is somewhere in Huay Xai, Laos. She has taken an overnight bus from another town and arrived exhausted and utterly lost. She’s been looking for a zip line park she heard about, but so far no one she’s asked has any idea where it is. And so she wanders, listless, through the city, hoping for some clue to materialize.

By chance, she drifts into a small shop. Surprisingly, the woman at the counter speaks perfect English, and even though she doesn’t know about the zip line park offhand, she makes it her mission to help Hermiz. After a while, she locates it on her phone. But instead of giving Hermiz the directions and sending her on her way, the woman asks her son to give Hermiz a lift there—but not before packing her a hearty breakfast for the road.

Catherine Huang

It is near the beginning of her trip, and Catherine Huang is still getting the hang of things. She has arrived in Eastern Europe anticipating that she’ll be able to hop on the region’s numerous and inexpensive trains for a whirlwind tour of the Baltics on the cheap.

What she encounters instead are trains that are closed off, canceled, or packed with thousands of Syrian refugees fleeing civil war and unrest in their home country. At one point, she becomes stuck on a crowded train for seven miserable hours. As she contemplates the delay, she realizes how grateful and lucky she is that she will eventually be free to continue on her travels, unlike so many of her fellow passengers.