This is an article from the fall 2017 issue of LSA Magazine. Read more stories from the magazine.

In 1992, Art Spiegelman’s Maus won the Pulitzer Prize. Then, in 2015, Cece Bell’s graphic memoir El Deafo won a Newbery Honor and the graphic novel This One Summer by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki won a Printz Honor and a Caldecott Honor — the first time comics had taken so many important national prizes for children’s literature.

Then, in 2016, March Book 3 — the final entry in a trilogy written by civil rights icon Representative John Lewis, congressional aide Andrew Aydin, and comics creator Nate Powell—won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. And while no cartoonist has yet received the Nobel Prize in Literature, it’s becoming easier to imagine.

These books tackle issues such as the Holocaust, deafness, family dissolution, racist disenfranchisement, and lynching — topics hard to imagine showing up in mainstream comics of bygone eras. The medium’s maturity makes it a heck of a lot more likely that you’ll hear a review for a new graphic novel on NPR than you were 20, 10, or even 5 years ago. (And the chances of that graphic novel actually being good might be better, too.)

“This is a pivotal moment in the field of comics studies,” says LSA alumna Elizabeth Nijdam (Ph.D. 2017). “I think everything is changing right now.”

‘None of us were talking’

Nijdam didn’t start reading comics until college, and she didn’t begin her research into comics studies in earnest until after she had written her master’s thesis. (It was on East German film.) But Nijdam loved using comics in the German language classes she taught, and was moved by how powerful they were as a tool for instruction and by the possibilities of the art form.

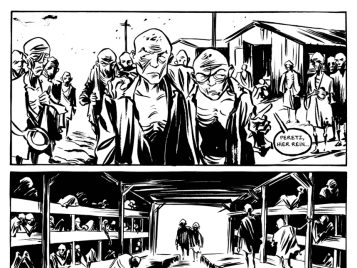

Nijdam’s research covers German comics and sequential art — including the artists and creators included in the slideshow at the top of the page — creators who channel multiple aesthetic traditions in their work, including German Expressionism and American alternative comics. Many contemporary German comics focus on the country’s history, Nijdam says.

“This movement really began internationally with Art Spiegelman’s Maus,” Nijdam says. “Parts of Maus date back to 1973, but it didn’t win the Pulitzer Prize until 1992. And that’s when people were like, ‘Whoa, you can talk about history in comics?’ Spiegelman really changed that for everybody.”

Nijdam founded the Transnational Comics Studies Workshop, a Rackham Interdisciplinary Study Group, to connect comics studies scholars across U-M. Last year, the group brought 14 speakers to campus and worked closely with a graphic narrative class taught by Phoebe Gloeckner, an associate professor in the Stamps School of Art & Design and the creator of Diary of a Teenage Girl.

Now, Nijdam is a member-at-large for the Graduate Student Caucus of the Comics Studies Society and the secretary for the International Comic Arts Forum. She also won the prestigious Swann Foundation Fellowship from the Library of Congress, where she presented her research in May 2017, and received Rackham’s Outstanding Graduate Student Instructor Award for her teaching with comics. She was recently awarded a postdoctoral fellowship that will allow her to live in Berlin for a year and work on her first book, a study of 12 contemporary German comics creators.

She says she is hopeful for the future of comics studies at U-M and around the world.

“I want to see the field continue to grow in an interdisciplinary fashion, and maybe one day have a center on campus,” Nijdam says. “I know that a lot of our work has been really well received by lecturers, faculty, librarians, and graduate and undergraduate students. The audience for our lectures is really diverse. And I hope that these amazing things continue to happen at the University.”