Nestled in the spectacular beauty of the Tatra Mountains, Zakopane is a vacationer’s dream. The highest town in Poland, it draws hikers and rock climbers to its pristine beauty and expansive views. In the winter, skiers and snowboarders come to take on its slopes or to watch the Ski Jumping World Cup. In their downtime, they can soak in the town’s charm: its historic wood chalets, its regional food and dialect, and its highland folklore.

This is the way most people know Zakopane: as a holiday resort. They don’t know the village also has a rich history as a haven for artists, musicians, and political activists—or that for 17 days it was an independent republic. LSA’s Copernicus Program in Polish Studies hopes to help change that.

On February 4, the Copernicus Program opens “100 Years of Polish Independence: Zakopane 1918,” with a lecture by journalist and mountain guide Maciej Krupa, and an exhibition of photographs from the archives of the Tatra Museum in Zakopane, Poland. The exhibition is on display in the International Institute Gallery in Weiser Hall until May 3, 2019.

The East and the West have fought over Poland for a thousand years and its fortunes have risen and fallen with the rest of Europe’s. But in the late eighteenth century, when it was invaded by Russia, Prussia, and Austria, the country of Poland disappeared from the world map until the end of World War I.

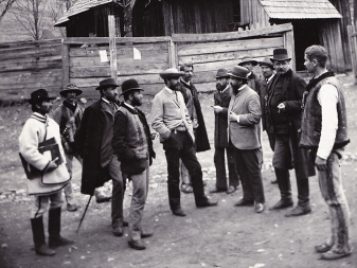

A few decades earlier, when Poland was still absent from the map, Zakopane was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The small highland village was having its own Belle Époque, drawing artists, intellectuals, social activists, and political figures to a village that had recently plumped with new pensions and sanitariums for people suffering from tuberculosis—and outside money. During this period, Zakopane hosted the Polish-born novelist Joseph Conrad; the writer and Nobel Laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz; the biologist Rudolf Weigl, who created the first effective typhus vaccine; the father of British anthropology, Bronislaw Malinowski; the chemist and physicist Marie Curie; and the pianist Arthur Rubinstein among many others.

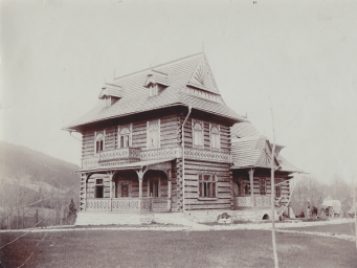

The nineteenth century architect, painter, and writer Stanisław Witkiewicz designed a villa in Zakopane in homage to the region’s traditional buildings. Its peaked, Swiss-style chalet was embellished with local motifs, such as geometric or botanical patterns that had been carved into the wood. It became the foundation for what is now known as Zakopane style.

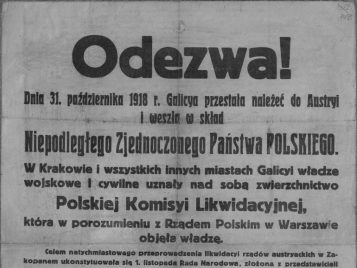

It was here that the Republic of Zakopane was founded on October 31, 1918. For the approximately 400 hours it existed, the Republic of Zakopane declared its loyalty to the independent state of Poland. Its citizens disarmed the local Austrian military police and then they elected writer Stefan Żeromski to be their president until the republic dissolved on November 16, 1918. Later, recalling his brief time in office, Żeromski said, “I held this unforgettable, absurd, and lofty office while Mommy Austria was collapsing into ruins. I solemnly swore in the army, the police, the snitches, the town council, the post office, and the telegraph agency, pledging them to loyalty to the new state. I even declared war in order to seize back the villages of Głodówka and Sucha Góra from a Czech invasion.”

Independence Day

Traditionally Poland observes November 11, 1918, as the anniversary of its independence, but, in fact, throughout the region during those tumultuous weeks at the end of World War I, there were many such proclamations. Zakopane’s was one of the earliest.

“They came together with a lot of hope and fanfare at the end of the end of the first world war,” says Geneviève Zubrzycki, Director of the Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia and Copernicus Program in Polish Studies. “We wanted to mark the centennial, but we didn’t just want to wave flags or host a panel to glorify the past. We’re a top program with top scholars that embrace the complexity of history, and this is how we wanted to recognize Poland’s centenary too.”

The Copernicus Program in Polish Studies has existed, in some form, since 1973, which makes it one of the longest-running Polish programs in the country – and one of the most cross disciplinary too. “We have people in sociology, Slavic studies, comparative literature, American studies, and on the music faculty,” Zubrzycki says. “Our interdisciplinarity informs how we approach Polish Studies. We build off each other.”

The program’s connections to Poland are similarly varied. They work with cultural foundations, such as the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, and various museums, such as Polin, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, and the Tatra Museum. The program also hosts scholars, artists, and political figures, such as Robert Biedron, the first openly gay elected official in the Polish parliament.

“What's cool about the Zakopane project is that it exemplifies the synergy between the Copernicus Program here at Michigan and what we do in Poland,” Zubrzycki says. “The Tatra Museum has provided the photographs for this exhibition, and we worked on telling the story. We're also developing our relationship with the museum by sending our students to intern there. Because our connections to Poland are so strong, we have our finger on the pulse and are able to offer dynamic programming.”

To use Zakopane as a lens to view Poland’s centenary is to both recognize the richness of Polish culture and to acknowledge what has been lost. That it became its own country exemplified its energy, its unified diversity, and its optimism. “It was unconventional place and project, to say the least,” Zubrzycki says, “it would be like creating a Republic of the U.P.”

During its time as a republic, Zakopane was a place where people of different ethnicities lived together: the Gorals, or highlanders; Catholics; Lutherans; Ukranians; and Jews—a very rare situation in today’s Poland. “Since World War II, Poland has basically become monoethnic,” Zubrzycki says. “It’s over 90 percent ethnically Polish and Catholic now. We’re trying to show that even in remote places like the Tatra mountains, this has not always been the case. Given the current state of Polish politics, it is important to show that diverse legacy.”

Zakapone Events

Mon, Feb 4, 2019; 5:30-7:00 p.m.

Lecture and Exhibition Opening. 100 Years of Polish Independence: Zakopane 1918

555 & 547 Weiser Hall, 500 Church Street, Ann Arbor

February 4 – May 3, 2019; 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m.

Exhibition. 100 Years of Polish Independence: Zakopane 1918

International Institute Gallery, 547 Weiser Hall

Wed, Feb 6, 2019 | 12:00 - 1:20 p.m.

CREES Noon Lecture. The Polish Athens: Zakopane as a Center of Polish Culture

555 Weiser Hall