When Oleg Grabar (Professor Emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton) was awarded the degree of Doctor of Humane Letters by the University of Michigan at its April commencement, the Kelsey was delighted to welcome back a most distinguished old friend. Grabar began his career in Islamic art and archaeology at the University of Michigan. He taught in the Department of the History of Art from 1954 and did fieldwork for the Kelsey Museum before leaving for Harvard University in 1968.

At Michigan, Grabar developed a remarkable following. Through his intellectual brilliance and his charismatic capacity to excite all levels of audiences, he established the fledgling field of Islamic material and visual culture in the U.S., putting Michigan on the map as the pioneering center for Islamic studies in North America. Between Michigan and Harvard he trained more than sixty Ph.D.s, who then went on to fill positions in museums and in academe and eventually to energize whole new generations of specialists.

While at Michigan, Grabar worked with the late Professor George H. Forsyth, Jr., then director of the Kelsey Museum. In 1956, Forsyth took a small group of colleagues on a reconnaissance expedition to the Middle East in search of good sites for excavation. Among the group was Oleg Grabar, as well as another person who holds a special place in the annals of Kelsey history: the late Fred Anderegg (our gifted and prolific excavation and small finds photographer for decades).

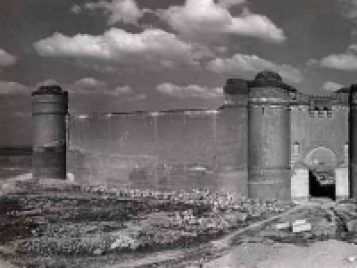

The reconnaissance party explored five countries, traveling along dusty, isolated desert tracks. Forsyth settled on the famous Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai (the Mount of Moses) as the site of his own multiyear project. Grabar fixed upon the equally dramatic—if less illustrious—site of Qasr al-Hayr Sharqi, in Syria. Both these projects flourished under the aegis of the Kelsey Museum.

Grabar worked at Qasr al-Hayr for five seasons in the years 1964 to 1971. He published numerous preliminary reports, including an extensive interpretive article in Ars Orientalis 8 (1970). He went on to publish a two-volume monograph on the site: City in the Desert: Qasr al-Hayr East (1978) with Renata Holod, James Knudstad, and William Trousdale.

When Grabar came upon the site in 1956, its majestic ramparts were partially (tantalizingly) visible as they projected up out of the drifting Syrian sands. The excavations eventually revealed that the site, located strategically in the semi-arid region between the Euphrates River and Damascus and at the foot of a key mountain pass, was a commercial installation that flourished in the eighth century CE, enjoyed a renewal in the eleventh century, and then was abandoned in the fourteenth.

An outer wall, meant to provide safety from bandits and wild animals, embraces the site in a circumference of almost sixteen kilometers. Held within this wall are two enclosures. The larger of these, measuring 160 x 160 meters with four axial gates, was an administrative center and elite living quarters. It incorporated an elaborate irrigation system, an area developed for agriculture served by these canalized waters, a mosque, a large bath, and olive presses. The smaller enclosure, with a massive wall of its own measuring 70 x 70 meters, served in its heyday as an enormous khan, or trading arena. It is the earliest documented example of this tradition of monumentalized trading installation that became a hallmark of medieval Islamic cities.

Qasr al-Hayr holds renewed significance for archaeologists, anthropologists, and social/economic historians who are increasingly concerned with the intersections of nomadic and sedentary life in the commingled pursuits of trade, agriculture, and pastoralism in this desert landscape from antiquity to the present. As a result of conversations with Professor Grabar, the Kelsey is committed to finding the means to support a project to catalogue the archives of his excavation fully and to make the material readily available for study.

When Oleg Grabar came to the Kelsey in April to visit the photographic archive and the records of his excavations at Qasr al-Hayr, I had the pleasure of spending time with him and his wife Terry (a Michigan Ph.D. in English literature who taught at Eastern Michigan University for many years). Also part of the group were Collections Manager and Curator of Slides and Photographs Robin Meador-Woodruff and a new Research Associate of the Museum, Professor Sussan Babaie. Professor Babaie, an Islamicist in the Department of the History of Art, is the new successor here to Grabar’s legacy in this field. We all had a marvelous time listening to our eminent guest reminisce about the trials and tribulations of work in a then totally isolated region (with no paved roads and no radio or telephone communication). As we went through photo albums of the local workers at the site, Professor Grabar had a story to tell about every one, it seemed. Sometimes they were riotously funny; sometimes they were poignant. Always they were touched with good will and a rich appreciation for the quirkiness in all of us. It was easy to see why, in the long litany of traits describing his worthiness for a Doctorate of Humane Letters cited by the President of the University, his lifetime dedication to the role of a truly engaged human being figured prominently. Grabar remains an inveterate ambassador between East and West as well as a scholar who has truly transformed a learned field of momentous significance to the history of civilization.

—Margaret Cool Root