What kind of lasting impressions have English faculty left on our students throughout the years? What follows below is a selection of the responses we received to this question from our alumni. Please send us your own by following the instructions on our submissions page.

.jpg.transform/xbigfree/image..jpg) Daphna Atias on Scotti Parrish

Daphna Atias on Scotti Parrish

—English 2006

In 2003, as an overambitious freshman, I stumbled into Scotti Parrish's 400-level class on the Environmental Imagination in American Literature. I'm glad I found her then: her genuine interest in her students' thoughts taught me to listen; her way of working from small moments to big ideas taught me to ask questions of texts; and her ability to synthesize our observations showed me how to begin to turn those questions into arguments. Scotti can take even the most seemingly dry, prosaic, and factual material and open it up so that it speaks to fundamental and fascinating questions about how we construct knowledge about the world and who gets to participate in that act.

This is what she does day in, and day out, with a serene, quiet confidence (never arrogance) that is, somehow, humble. She makes teaching look easy while still honoring its difficulties. But perhaps what I remember most are the moments that departed from routine: the day, for instance, when the U.S. invaded Iraq and when we spent 45 minutes just talking about it, fifty people in a classroom doing with the world around us what we had been taught to do with texts: ask questions; consider different interpretations; dwell in that feeling of unsettledness; and listen to each other, often emotionally yet never confrontationally. Or, more locally, the day before a department meeting about the structure of the English major when she spent over an hour polling her junior seminar about every question on the agenda, promising to share our thoughts with her colleagues. Scotti approaches her students with deep interest and compassion, and, in so doing, models for those students how to appreciate and genuinely engage with texts and with each other. When I graduated with a B.A. in English and Political Science in 2006, I became a high school English teacher and tried, daily, to live up to her example. Back at Michigan now, working on a Ph.D. with Scotti as my advisor, I still do.

David Baum on Ralph Williams

David Baum on Ralph Williams

—English 1986

I am certain that I would not be writing this piece at this particular desk at the University of Michigan today were it not for the Shakespearean Drama course I took in the fall of 1983 as a sophomore in LS&A. The class was taught by the magnificent and inimitable Ralph Williams. I had read a bit of Shakespeare during my senior year in high school and enjoyed it; by the time I finished Professor Williams’ class, Shakespearian drama had become my academic passion. It was best to arrive five minutes early for class each morning so as not to miss Professor Williams energetically springing into the room, greeting us with a lively and cheerful, “Good morrow and rich welcome to you!” I found myself captivated each and every class by Professor William’s insightful and spot-on analysis, which invariably included expressive, theatrical readings from the plays themselves. To this day, chills run up and down my spine as I recall Professor Williams speaking those painful words with furrowed brow and crestfallen face, uttered by the broken Othello: “But yet the pity of it, Iago! O Iago, the pity of it, Iago!”

Inspired by that class, I declared English as my major. I wrote an undergraduate thesis focusing on King Lear and Othello under Professor Williams’ supervision . . . what a pleasure and an honor that was! I know that my work as an English major was a primary reason that I was admitted to the University of Michigan Law School, to which I was able to return as an administrator after six wonderful years of law practice, and where I have remained for the past 16-and-a-half years. I will never forget – and be forever grateful to – Professor Ralph Williams, who helped provide me with the most exciting and interesting undergraduate education for which one could hope and enabled me to lay the foundation for what has been a marvelously satisfying career at one of the greatest institutions of higher learning in the world.

David Baum

BA ’86, JD ‘89

Assistant Dean for Student Affairs and

Special Counsel for Professional Skills Development

University of Michigan Law School

Walter K. William Butzu on Emily Cloyd

Walter K. William Butzu on Emily Cloyd

—English 1992

I completed a BGS in 1992, and even before graduation, I was hired to teach upper-school English at University Liggett School, a private high school in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. I have just completed my twentieth year of teaching English at Liggett, and for the last six years I have served as the chair of Liggett’s English department. I had several excellent English professors during my undergraduate years, and I could write encomiums for each one. Dr. Mullaney, Professor Leon, Dr. Beauchamp, and those dear, dear men, Professors Shulze and Schoenfeldt, all ranked high on my list of great instructors, but Dr. Cloyd is one professor who continues to influence me beyond the excellent course she taught.

Professor Cloyd was my Core I instructor. If memory serves, Core I dealt with British literature before Shakespeare. I remember well Dr. Cloyd reciting sections of The Canterbury Tales in Middle English. What an accent! I still get a bit of a chill thinking about that sickly woman seeming almost to grow in stature and recover her strength as she recited that text. I can still quote, almost verbatim, parts of her syllabus as she cleverly offered the class a few directives of which to be mindful when writing essays. But the greatest lesson I learned from Professor Cloyd happened many years after I had graduated. The then-still-in-print Ann Arbor News published an article listing all the famous literary people who had spent time on the University of Michigan campus. Arthur Miller, Robert Frost, W.H. Auden (I think), and a host of others were named. A couple of weeks later, a long letter to the editor appeared in the Ann Arbor News chastising the writer for failing to include the poet Robert Hayden. I had just been dealing with Hayden’s great poem, “Middle Passage,” in preparing to teach Charles Johnson’s novel of the same name (a fragment of the Hayden poem appears as an epigraph in that excellent novel). I read the letter to the editor with keen interest because I had no idea that Robert Hayden was associated with the University of Michigan. When I finished reading the letter, I noticed that it had been contributed by E. Cloyd. I emailed Dr. Cloyd hoping that she was indeed the Dr. Cloyd who had taught me (she was so sickly in the late 1980’s that I was almost certain that this must be a different E. Cloyd). I wrote her about my interest in Robert Hayden and thanked her (if I had the right E. Cloyd) for both her excellent teaching years before and her insightful letter to the editor. Several days later I received a wonderful and expansive reply telling me about her professional relationship with Robert Hayden. They had found support in each other as they worked to find their voice in an English faculty then quite dominated by white males. I saved her email, and I read parts of it to my classes when I teach Robert Hayden’s poetry. I was saddened to learn that Dr. Cloyd passed away this January, and I feel fortunate that I had the opportunity to thank her for her teaching. That opportunity only came about because Dr. Cloyd, well into retirement and well into her 70’s, was still working tirelessly to set the record straight on behalf of her talented colleague and excellent friend, Robert Hayden.

Walter K. William Butzu

Chair of English Department

University Liggett School

Jill (Vining) Donovan on Macklin Smith, June Howard, Ralph Williams, Thomas Garbaty, James Anderson Winn, and Bert Horback

Jill (Vining) Donovan on Macklin Smith, June Howard, Ralph Williams, Thomas Garbaty, James Anderson Winn, and Bert Horback

—English 1989

My name is Jill (Vining) Donovan and I am a 1989 graduate of the Honors English Program at Michigan. I have taught high school and college English for 24 years and am currently an administrator and teacher at John Burroughs School, an independent school for 7th-12th graders in suburban St. Louis, MO.

As a first-generation college student who spent my first few weeks on campus walking around in a kind of confused fog, my years in the English program were formative in all kinds of ways. Not only did I learn an approach to literature that I still embody today, I learned to recognize and celebrate the unique gifts in myself and the people all around me.

While my list could stretch longer, I want to mention six professors in particular who made an impact on me. I was a student in Macklin Smith's Introduction to Poetry course in the fall of 1986. Still a profoundly shy student, my heart would pound before I even raised my hand to make a comment. I had smart things to say, but was, quite simply, too afraid to say them. One day Professor Smith read my page-long, hand written explication of a single line of poetry aloud to the entire class. I wasn't necessarily less afraid to speak after that day, but I knew that when I did summon the courage to speak, my words would add value.

On a similarly empowering note, I want to credit June Howard who taught a 300-level American Literature course that I took the following spring. As a sophomore in a course populated mostly by very verbose (and to my mind very sophisticated) juniors and seniors, I was stricken silent in this course from the get go. I did all of the reading, earned A's on all of my essays, posted to the class weblog (yes, Professor Howard was a pioneer in this respect), but on my final paper received this comment: "While you should have earned an A in this course, your grade is a B. You cannot remain silent and earn an A in a literature course." I still remember standing just outside the backdoor of my family's Kalamazoo, MI home and reading that comment on the final essay mailed back to me. I was chastened, but knew that she was right. I have never begun a class without telling them this story. I tell my students—all of them—that they need to say something, anything, during the first week of class—that they need to establish themselves as speakers right from the start. Professor Howard taught me that.

I took Ralph Williams The Bible as Literature course as a junior in the fall of 1987. Although there were 150 students in that lecture hall, Professor Williams took the time to greet all of us in great sweeping waves at the opening of each class. He would dance up and down the hallways, swinging his giant hands back and forth, and saying, "good morning and a rich welcome to you!" From him I learned the critical importance of "collecting" my students, of gathering them as human beings in a learning community before diving into the day's agenda. I also learned several phrases about the OT God that have never left me including this one: "He can create, and he destroy." I've reflected on Professor Williams off and on for more than two decades. Because I lived in an apartment on S. Forest near the pre-school where he picked up his tiny son, I often watched him as he bounced along the sidewalks with his boy atop his shoulders. The very best lesson he taught me was to seize and model joy.

I had Thomas Garbaty for Medieval English Literature in the fall of my junior year. From Professor Garbaty I learned the importance of knowing every student's name. "Names are important," he told us, and I remembered that. I also learned that it's okay for a teacher to be visibly moved by literature. Garbaty teared up when talking about the moment in the miracle play when Abraham, while climbing the mountain to sacrifice Isaac, says "don't tell his mother." His emotion evoked mine: another lesson I have never forgotten.

James Anderson Winn taught 18th Century literature to me and my Honors English cohorts in the spring of our junior year. He was appalled at our lack of historical knowledge and spent many class periods lecturing to catch us up on all we'd clearly missed in high school. He also paid us the very steep compliment of expecting something very polished in our analytical papers. I paid close enough attention to his written feedback that I still have by memory several of his quite acerbic but very helpful suggestions.

I could write for a very long time about Bert Hornback. I spent 9 weeks with him and 11 other students in England and Ireland during the spring of 1988 on a literature study trip that has shaped me more profoundly than I can probably say. Bert taught me to pay attention; he taught me to take responsibility; he taught me to finish what I start; he taught me to keep on giving. He taught me that literature and teachers really do change lives. Bert was my advisor during my senior year when I wrote my honors thesis on the poetry of Donald Hall. My peers and I would bring drafts to Bert's house where he would sit in a rocking chair reading them and then comment. After staying quiet for a long time on my first visit, Bert paid me one of the best compliments I ever received as a student and young writer. "Where did you learn to write like this?" Bert asked. I try to empower my own students in the same way.

Steve Glaser on James Gindin

Steve Glaser on James Gindin

—English 1987

My name is Steve Glaser, and I am a 1987 graduate of the LSA English Honors program. I am a pediatric ophthalmologist in the Washington, D.C. area (Rockville, Maryland) where I live with my wife and four children. I was fortunate to have been taught by a number of outstanding professors at Michigan including Ralph Williams, Jim Gindin, and Bert Hornback.

I still savor the days as a freshman at Michigan, coming to the MLB classrooms with anticipation and excitement on crisp autumn mornings. Listening to Honors Great Books (191 and 192) lectures freshman year taught by Professors Buttrey, Cameron, Hornback, and others, quickly set the stage for a lifetime of admiration for my alma mater, and painted a clear picture of what the college experience was supposed to be. We debated the meaning of the adjective "modern" in "MLB." Was it "modern language," i.e. English, German, and Spanish—not Sanskrit, Latin or Greek? Or did it mean "modern building" since it seemed like a fairly new building, architecturally modern—not like the old buildings, Angell Hall, or Haven Hall, where I took other English classes.

Professor Gindin was the chair of our Department of English when I was at Michigan. The first time I had him for a class, I was naturally very intimidated. Very quickly, Professor Gindin put me at ease with his soft, nurturing, paternal ways. Clearly his breadth of knowledge was immense, but he never made me feel stupid, and always had time to take me into his office and discuss whatever questions I had about class. I remember that he took our Honors English class out for some food and drink at a local restaurant where he very politely asked if anyone minded if he smoked. This seemed to put us all at ease, and I remember thinking what a cool guy, this uber-educated man was, and that he really cared about us, and wanted us to succeed.

I was graced to have Professor Bert Hornback for several classes as an Honors student at Michigan. Professor Hornback was the single most influential professor I had at Michigan. At the start of many of his classes we would write our "Squibbles" prior to the actual class lecture and hand them in. Squibbles were our thoughts about what we had read the night before. They were informal, but Professor Hornback took the time to critique every Squibble, and make sure you know exactly where he stood on all of the topics he taught us. I have fond memories of going to his house in Ann Arbor, "The Blunderstone Rookery" near The Arb, drinking Guinness on tap, while discussing literature, philosophy, and politics (when we were 21 or older, of course). In addition to teaching some Great Book classes, Professor Hornback taught a Dickens class (some of us thought that he thought that he really was Dickens!), and the one that had the most impact on my life, "Words." "Words" used the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) that we had to purchase in the mini-print version (not so good if you are in your 40s, like I am now). To this day I enjoy looking up the origin of English words with my family to help us better understand the historical context and relevance of a word. Professor Hornback is currently teaching in Germany and I would be thrilled to have him come back to Ann Arbor.

It is hard to believe my oldest is only a few years away from college. I am pleased that he is in an honors humanities, pre-Michigan program at our local high school, where he is taking Latin, Honors English, and AP history. I hope he and my other three children will have the opportunity to have an enriching, inspirational college experience like I did during my tenure as an English major at Michigan.

Go Blue! "Those who stay will be champions."

Laura Hlebasko on William (Buzz) Alexander

Laura Hlebasko on William (Buzz) Alexander

—English 2011

My name is Laura Hlebasko. I am the proud holder of a B.A. in English, conferred upon me in 2011.

During my senior year, I took two consecutive semesters of classes with Buzz Alexander—the first was English 411: Prison and the Artist. The second was English 326: Community Writing and Public Culture, also known as the Portfolio Project.

The magic of Buzz’s classes lies in what happens not between the pages of a book, but around a circle of people. His subtle and provocative questions about what we had seen, read, and experienced of injustice made for some of the most challenging and important conversations of my college career. These conversations stuck with my fellow students and me long after class was over.

The particular lesson I take with me, and that I think about constantly, is that you have to believe something special can happen when a group of people, any group of people, comes together. Because what unites us is greater than what separates us. I try to go into every situation, no matter how “cool” or “uncool,” worthwhile or discard-able my mind wants me to believe it is, with this outlook. It has made my life and relationships richer, and comprises a major part of the legacy I want to leave behind. Thanks Buzz, for showing me what it means to be a brave learner, and a brave person.

Diane Namm on James Gindin

Diane Namm on James Gindin

—English 1980

My Memories of James Gindin OR Everything I Needed To Know I Learned From Jim

Professor James Gindin was my Master’s Thesis Advisor, my teacher, my employer (I was his TA for a year), and ultimately my friend. I jokingly refer to my English MA as my “psychology of directing degree”—but many a truth is said in jest. I can still hear his gravelly voice in my head, and imagine him sitting at the head of a student seminar circle, a cigarette elegantly in hand, curling smoke backlit by the sun coming through a classroom window.

Although he didn’t suffer fools lightly, Jim was patient and respectful of his students, grads and undergrads, whereas, I, as an inexperienced TA, was sometimes impatient and dismissive. Actors, like English students, do their best work when they feel safe and respected. That was Jim’s teaching style; I’ve made it my directing style, and I’m grateful to him for it every day.

When analyzing an author’s work, he would focus on the craft: “There are no wasted words. Everything is there for a reason. Peel back the layers, look for the symbolism, pay attention to the dialogue, choices, actions—the descriptions and the settings. That’s how the author reveals her intentions.” It’s been thirty years since he spoke those words. They inform my writing daily.

My one regret, after all these years, is that I never got the opportunity to thank him for all he taught me. He died before I became a filmmaker. So when I learned that there was a Screenwriting Fellowship Program in his name, I knew that was the one way I could demonstrate my gratitude, to the University and to Jim, because it’s true: everything I needed to know I learned from Professor James Gindin.

Sarah Prensky-Pomeranz on Theresa Tinkle

Sarah Prensky-Pomeranz on Theresa Tinkle

—English 2011

My name is Sarah Prensky-Pomeranz. I graduated from the University of Michigan in 2011 with a BA in English and two minors in Urban and Community Studies and Medical Anthropology. I am currently an AmeriCorps Youth Worker in Boston and am heading to South Africa in 2013 on a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship grant, where I will be teaching English and implementing a soccer and creative writing program for girls.

As a UM English major, I learned how to write. And I learned how to think. I learned how to tell stories that draw in an audience, to be whimsical with language and to draw inspiration from a single sentence. I learned that there are no axioms in literature and that words not only convey speech, but speak for themselves.

I learned all of this from a collaboration of classes and professors, but one professor in particular empowered me to discover that literature can also be playful.

In the 2011, I took three classes with Professor Theresa Tinkle. During Winter Term, I took “Sex and Medieval Literature,” and in Spring Term I took both “Early Women Writers” and “Sex, Gender and Religion.”

By senior year I still had not filled my pre-1600 requirement and I admit, I was not thrilled to have to take a pre-1600 class. But in Winter Term of 2011, I tentatively registered for Theresa Tinkle’s “Sex and Medieval Literature.”

I have never laughed so much in a ninety-minute class period, let alone a class period focused on twelfth century literature.

This laughter did not just stem from Professor Tinkle’s quirky humor and marvelous laugh, it more so came from deep understanding. With Professor Tinkle’s guidance, I learned to see all literary pieces as palimpsests teaming with subtleties, beauty and humor. I learned that a narrator can be unreliable and deceiving, even one crafted in the twelfth century. I learned that women can be men, sex can be hilarious, God can be illusory and servants can be the most powerful of characters.

I learned all of this because Professor Tinkle created a dynamic learning environment to facilitate an appreciation of the literary pieces we were studying. In class, I was out of my seat as much as I was in it, acting out scenes from the York Plays and Latin Comedies. We examined art pieces that enriched the literary pieces, analyzed primary source epistolary collections and wrote essays with the most subtly profound theses.

As an alumnus, I continue to feel Professor Tinkle’s influence. Professor Tinkle pushed me to think deeply, and I strive to do so every day. She role modeled how to both live and think poetically and to approach things with humor and creativity. Her impact on me further confirms my desire to become an English teacher myself, and I hope to be one like Professor Tinkle who celebrates nuances, fills her classroom with laughter and fosters a love of literature in her students.

Robert Prouse on Frank Huntley

—English 1970

So there I was a Freshman in 1966, and required to take a class with a title something like “History of English Literature”. It had the familiar structure of a weekly lecture by a Senior Professor, and then a couple of seminars each week typically run by a graduate student. It was my great good fortune that the Senior Professor was Frank Huntley. It was my even greater good fortune that when I showed up at the first seminar session (which I had selected for its convenient time slot in my schedule), there was Professor Huntley. He explained that he enjoyed teaching so much that he made a point of always taking at least one of the seminar positions. The following semester, most of us in that seminar section made a point of signing up for anything Professor Huntley was scheduled to teach. It turned out to be Early Twentieth Century Poetry – which I probably would not have selected otherwise. Our major task that semester was a close reading of T.S. Elliot’s “The Wasteland”. We didn’t finish, and we collectively asked if he’d be willing to get together with us the following semester on an informal basis to finish. He not only took us up on our suggestion, but invited us to his house. Mrs. Huntley baked cookies on the nights we came.

That semester The Beatles released “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”, and we asked him if we could study the lyrics in the same way as we had been doing with The Wasteland. He happily consented, and I still have a picture of this distinguished professor in all his tweediness, tapping his foot in rhythm to Sgt. Pepper.

This whole experience with Professor Huntley was a large factor in my decision to become an English Major.

(Professor Frank Huntley was on the U of M faculty from 1945 to 1973. In 1977 we was designated Professor Emeritus)

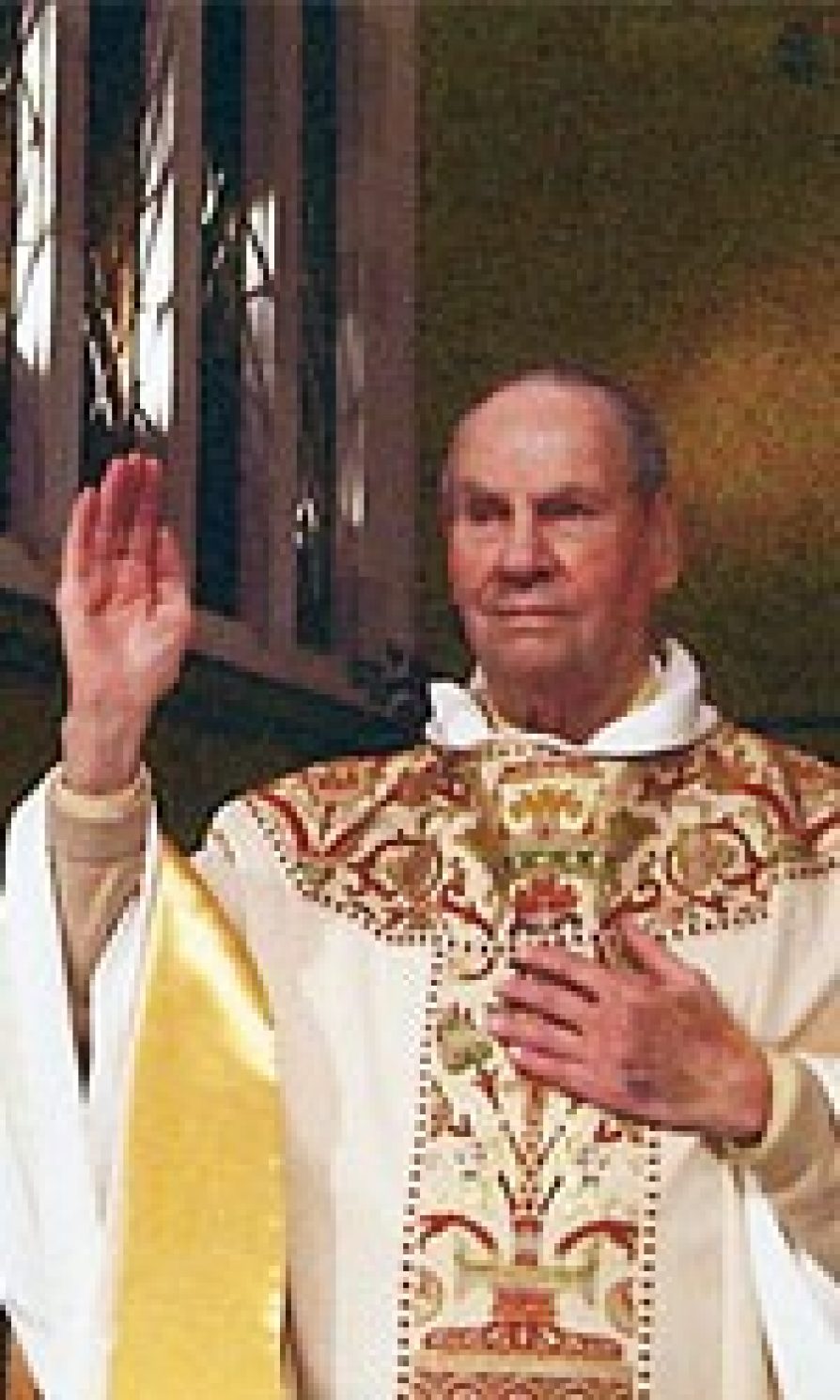

Lew Towler on Mary Needham

Lew Towler on Mary Needham

—English 1950

My name is Lew Towler. I am often referred to as Father Lew, because I am an Episcopal Priest and am presently, after two retirements, serving at St Andrew's Ann Arbor, the Church I first entered as a Freshman in 1946 (after three years in the U.S. Navy SeaBees) I received my A.B. Degree with most of my studies in history and English in 1950, went to Germany to study at Heidelberg for a year, returned to the University for an M.A. In Comp Lit (English and German) and then went off to Union Seminary to study with Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich in preparation for ordination.

The name “Needham” was just a name in the then used syllabus of courses offered each term. The name appeared opposite English 45, a course in American Lit. When I entered the assigned classroom for the first time, I was pleasantly surprised to see that Needham was a Miss or Mrs. Needham, and it didn't take me long to realize I had discovered a winner. During one class, I noticed she was wearing a small military ribbon on her dress. When twenty or so students simply left at the end of the period, I stayed and asked her about it. She replied that she and her husband (now no longer living) had worked on the relationship between French and English literature after WW 1 and that they were decorated by the French government. I thought that was pretty classy. Of course, we read Moby Dick and followed that with Billy Budd.

If it is possible to fall in love with a book (and I think it is) I went head over heels for the story of Billy Budd. So much so, that I wrote a brief piano composition which I titled, “Theme and One Variation on Billy Budd.” After I finished it, I stopped by her office, asked if she would cross the street to the Union where I played my first and only composition for her.

When, in my senior year I was trying to decide whether to dedicate my life to music, teaching or ministry, Mrs. Needham suggested that perhaps I needed a year to sort things out. “Have you thought about spending a year at a University in Europe,” she asked me. When I replied that I had not thought of it but it sounded like a nice idea, she asked me what facility I had in languages. I replied that I had 20 hours of German. Her next words, “You should go to Heidelberg,” inspired me to go there and then return to UofM for a Master's in Comp Lit. It was during that year that I decided ministry was my number one choice, and I then entered into theological studies.

In answer to the question posed for this essay, I could have mentioned Herbert Barrows, or Joe Lee Davis or Robert Super, all of whom were very important in my Michigan years, but I chose Mary Needham for the inspiration she gave me first to study in Germany and then to serve God and people in the ministry. My devotion to her memory is very strong, and, every Christmas I give flowers at Saint Andrew's in her name.