As a teenager in the public library of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Scott Ellsworth, now a lecturer in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies (DAAS), came across a brief account of a riot that had happened in the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa on May 31, 1921. Ellsworth, who had lived his whole life in Tulsa, had heard stories about the riots, but never in a classroom. Even at the library he couldn’t find much information about it. Over time, his curiosity intensified. In 1975, he made the riot in his hometown the subject of his undergraduate thesis, and he scoured the Tulsa library’s archival records for information. He found local newspapers from 1921, but in editions printed just before and after May 31, sections of the paper had been cut or torn away. Clearly, something terrible had happened in Greenwood, but why was there no information about it?

On May 30, 1921, a Black teenager named Dick Rowland entered an elevator operated by a white teenager, Sarah Page. The next day, the Tulsa Tribune reported that Rowland had attempted to rape Page, though Page never pressed charges and Rowland was later exonerated. The paper also ran an editorial that called for Rowland to be lynched.

In the early hours of June 1, a white mob—many who had been deputized and armed by city officials—assaulted the Black community of Greenwood. They looted businesses and burned over a thousand homes and churches to the ground. Some Greenwood residents reported that airplanes dropped turpentine balls, turning entire city blocks to flames. When the National Guard arrived to quell the riot shortly after 9 a.m., most of Greenwood’s 35 blocks had burned and almost 10,000 people were homeless. Official statistics recorded 10 white and 26 Black people died during the massacre, though that number has since been credibly revised to be closer to 300 deaths.

But in July 1921, a month after the massacre, a grand jury had concluded that “there was no mob spirit among the whites, no lynching, and no arms.” References to the massacre had been scrubbed by the city of Tulsa, then formally encoded into a journalistic style guide by order of the police commissioner. If mentioned at all in a textbook, it was in a single-line description of a Black mob. Ellsworth encountered reluctance in both Black and white people when he approached them to ask about their memories of the event. They had good reasons to leave the story out of their personal histories—shame, PTSD, fear of reprisal, worry about passing this painful story on to future generations. The silence helped to keep the story buried, and when it was finally uncovered, it became known as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

It’s taken Ellsworth 45 years to uncover and put the pieces together. Along the way, Ellsworth has found that “[This story] is not just a Tulsa story, it’s an American story. I hope it gets people to think about their own histories. What are the stories that we don’t talk about?”

Making the Map

In 1975, in order to understand the scale of the loss, Ellsworth constructed an enormous map of Greenwood using xeroxed city planning documents, scotch tape, and ballpoint pen. In The Ground Breaking, he recalls how the map helped him apprehend the scale of the loss. “No longer was it thirty- five square blocks or eleven hundred homes and businesses that had been looted and burned. Now the losses had a name. They were Mary Hoard’s hair salon, Arthur and Annie Scarbough’s tailor shop, and Dr. Travis’s dental office...The city directories weren’t some soulless, bureaucratic volumes filled with names and numbers. They were a ticket to help me resurrect a lost world.”

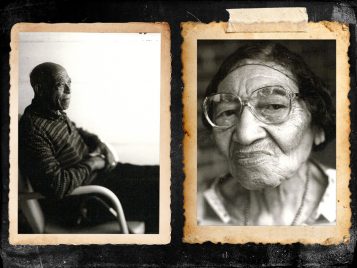

Ellsworth, at the beginning of his research, in Tulsa, 1975. Photo courtesy of Scott Ellsworth.

Before the massacre, Greenwood had been the joyful and bustling “Black edition of the American Dream” and was commonly called the Black Wall Street. Ellsworth was a white Tulsan, and at the time he began his research, “a skinny 20-year-old hippie.” Most white city officials had nothing to say to him. Some angrily denied that a riot even happened in 1921. One blamed the riot on “indians and Mexicans.” Ellsworth had to earn the trust of survivors and their descendants in order to do this work. A friend connected Ellsworth with one of the survivors of the Greenwood massacre, someone who was ready to share their story. Ellsworth listened.

Over the next months and years, he connected with other survivors. Ellsworth’s work rests on more than 40 years of relationships he built with the survivors of the massacre and their descendants.

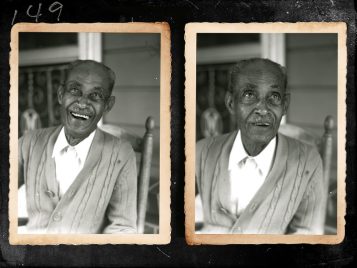

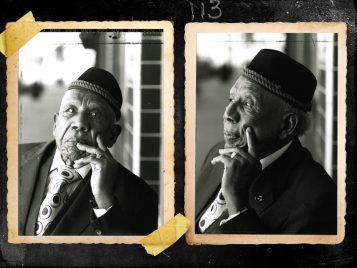

The library archives gave Ellsworth the map, but the survivors brought the map to life. There’s Mabel, the spirited elder who refused to talk with Ellsworth until the end of her life; Elwood, who appeared in a cemetery at dark to tell his secrets; Dick Rowland, who had stepped into the elevator that fateful day; tall and elegant George Monroe who was an unforgettable orator; Don Ross, a wise-cracking teenager turned state legislator and founding member of the Tulsa Riot Commission; and many memorable more. This vivid constellation of characters is the pulsing heartbeat of Ellsworth’s work. “None of this would have happened without them,” he says. The survivors and their descendants also led Ellsworth to his next stage of research: to unravel the mystery of the dead.

Unearthing

The research that Ellsworth began in the summer of 1975 eventually became his first book on the Tulsa Massacre, Death in a Promised Land (1982). When Ellsworth began writing The Ground Breaking, no one knew how many people had been killed during the Tulsa Massacre, or where the bodies were buried. Ellsworth collected incomplete facts, contradictory records, and childhood memories. A report from a visiting medic in 1921 reads, “The number of dead is a matter of conjecture. Some knowing ones estimate the number of killed as high as 300, other estimates being as low as 55. The bodies are hurriedly rushed to burial, and the records of many burials are not to be found.”

In order to find out how many were killed and where the bodies were buried, Ellsworth needed to ask the survivors how they felt about him pursuing these questions. Reopening the ground, Ellsworth knew, might also reopen wounds. The community gave him their blessing. Ellsworth began working with anthropologists and forensic scientists, collecting hundreds of testimonies, digging in the Oklahoma dirt, and studying bones. As lead scholar for the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, he says he spent the next several years like a detective, “Following leads. Chasing rumors. Dowsing for the truth.”

Our present continues to evince the past, and that’s why a rich and critical teaching of history is so important, Ellsworth says. “Some of the things happening now, like racial violence against citizens, have happened for a long time and we just haven’t talked about them. This is why our history is so vital. We have to get to a common understanding of our past in order to agree on the facts of the present—we have to listen to each other.”

Saige Porter, a rising junior and a biology, health, and society major, first learned about the Tulsa Massacre the summer before she took Ellsworth’s course, The Tulsa Race Massacre. She had been following the Black Lives Matter movement on social media. Like Ellsworth 45 years earlier, Porter was surprised that she hadn’t encountered this history before.

“As Black students,” Porter says, “we recognize things. We see how people treat us. In this class we recognized what our grandparents and our parents went through and what more work we have to do.” As upsetting as the course material was, Porter says she came away from the course feeling empowered as a Black woman and future doctor. Learning this history gave her a sense of purpose. “Doctors don’t have a lot of Black representation, and there’s a jarring difference in the quality of medical care that Black people receive. I have the power to treat others the way they want to be treated. I hold the power to be of service.”

Grateful acknowledgement is given to Fred Conrad, whose portraits of survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre were taken for the New York Times and are a part of “Unearthing Tulsa,” from UMMA's "Unsettling Histories: Legacies of Slavery and Colonialism" exhibit that takes untold stories of the historical erasure of Black Americans and explores photography’s role in making visible people and histories that have been actively suppressed.

.png.transform/reg/image.jpg)